Hello, everyone. I’m Rok, Event Architect, facilities manager, professional musician, and baker of cakes. When I was asked to write for this blog with its recent focus on STEM, I wondered how I would approach it since I‘m not a developer – mobile apps still seem like voodoo wizardry even after four and a half years at Detroit Labs. I finally decided that perhaps I was a woman in tech after all, my particular skillset focusing on the care and support of developers (you know, nerd herding). I further reasoned that since the first discipline of STEM was science, I could discuss an event in April of 2015 that propelled me into an obsession with all things neurological. It’s a very compelling tale, done in five parts, and at the end you’ll know how truly resilient the brain can be and how wildly complicated are its workings.

This story starts with pain.

It woke me early on a Wednesday morning, just as sunlight was filling the bedroom. It was like someone was hitting the top of my head repeatedly with a blunt piece of wood. Rivulets of agony streamed down the sides of my skull like hot lava and I whimpered quietly, hoping not to wake my husband. I convinced myself that it would be gone once I woke up, if only I could endure the next five minutes until sweet unconsciousness rescued me. Sure enough, there was no sign of it when I woke and I went into work as if nothing happened. This lasted for three days. I basically ignored it because it would always be gone once I woke up the second time.

On the fourth day while on errands, my thoughts suddenly became extremely dull and muddy. I found that I couldn’t remember if I had paid for my prescription as I came out of Costco and I was so tired, and my car seemed hopelessly far away. Did anyone notice how slow and zombie-like I was walking? I finally got to my vehicle, and looked back at the building. To my wonder (and delight), I saw something like this:

The entire length of the building had a bright, multicolored, zigzaggy line from top to bottom. All I could think was, ”Wow, that is so cool!” But I was in an exhausted stupor and already dreading the concentration it was going to take to drive home. I went to bed as soon as I walked into my house. The mysterious beautiful image returned briefly, dancing across my bedroom floor. Again when I awoke my symptoms were gone, so I thought no more about it.

By the fifth day, I had to pay attention. It was Easter Sunday and I had stopped at a gas station on the way to pick up my mom and grandfather for brunch, and once again my thinking was slow as molasses, and I barely recalled paying for gas with my credit card as I started my car. And then my right leg refused to move to the pedal. I had to think very loudly in my head like a drill sergeant, “Put your foot on the brake pedal! Now step on it while you change gears! Now move to the gas pedal! Now move it back to the brake!” Well, this is pretty serious now, I thought. I’m endangering myself and other people if I keep driving in this state.

So I asked my mom to drive to the restaurant. I suppose I kept denying that something was wrong, but not for much longer. My husband and mother insisted I go to emergency after I disclosed my symptoms to them, and so Easter brunch wrapped up quickly. We were off to the hospital with just the necessities, but I didn’t expect to stay overnight, although I brought my work laptop anyway. I was positive it was going to be nothing – I was just making my husband and mom happy by agreeing to get looked at.

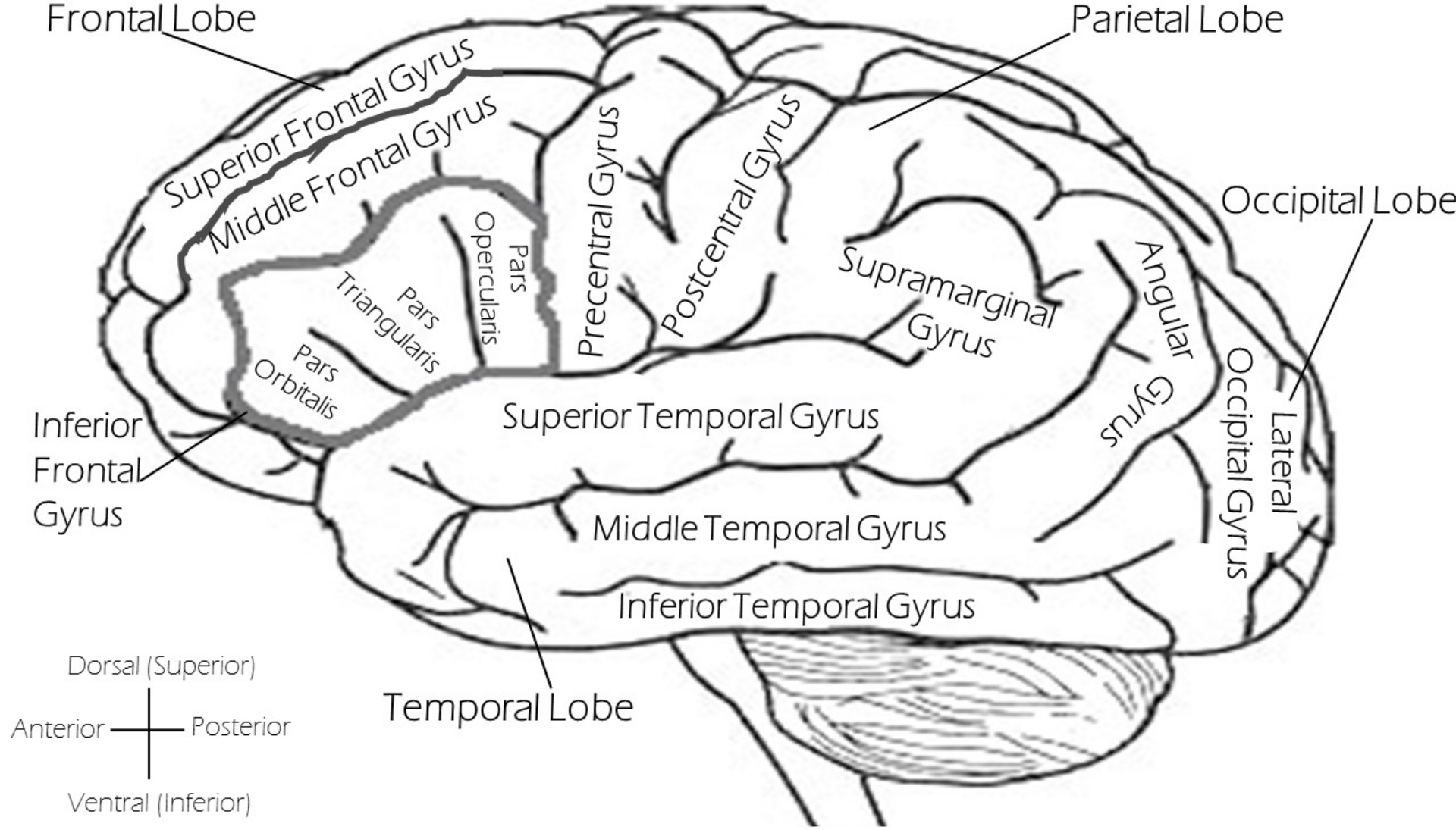

Who knew the CT scan would reveal a mass over my left frontal lobe?

The emergency room doctor said it looked like a meningioma, a benign brain tumor. This would explain my difficulty speaking, as it was on top of the speech centers of my brain. He had contacted the brain specialists and we would know more in the morning. Then he asked if we had any questions, but we were understandably too stunned to have any. Instead, I chose to do sensible, practical things, like text the founders of Detroit Labs about why I wouldn’t be coming in the next day. I also started thinking of all the music and baking obligations I suddenly wouldn’t be able to fulfill.

They gave me Decadron, a corticosteroid to control the brain tissue swelling, which burned fiercely as it entered through the IV in my arm. Then I was admitted to the neurological wing of Royal Oak Beaumont. An MRI would be performed early in the morning to get more details.

The next day, I was visited by Dr. Holly Gilmer, a very well-respected neurosurgeon who told me she was taking my case and explained what she saw in the MRI: very likely a meningioma, which under normal circumstances can be left alone but due to its size and location would have to be removed surgically the next day. She couldn’t tell if it was one or two tumors, and also it looked like it had grown into a section of my skull. That section would have to be removed and replaced with a titanium plate. At the mention of “titanium plate” I started laughing. I just had to, it just sounded ridiculous and unreal. Dr. Gilmer seemed genuinely surprised by my response, as I’m sure she was expecting some kind of emotional meltdown. Maybe it was my way of dealing with it, but it just sounded outrageously funny.

I spent the rest of my day emailing work (Subject: “Best Excuse to Avoid Opening Day”) and friends and cake customers. I wasn’t sure how I’d come out of it, though I was assured it would be successful as far as removing the tumor. (Would I lose all of my high school memories if she sneezed while operating? God, I hoped so). I told certain people to come visit, just in case I was a drooling vegetable after. We all had a lovely time in the waiting area. Then I was whisked away to pre-op.

A few hours later, a craniotomy was performed and a tumor roughly the size of a baseball was removed, thrown in a canister, and sent off to pathology to determine if it was good or had evil intent. I had spent my time in surgery floating in a profound darkness, simply existing and having no thoughts to disturb the silence. For a brief moment I had opened my eyes and seen a group of people through a window talking, but I thought it was closer to an anesthesia-induced dream than reality. I finally woke up, very awake and quite disoriented. Soon I remembered where I was and what had happened. I’d had brain surgery, I was in ICU, and my journey of recovery was just beginning.